When Art Turns Scripture into Myth: The Theological Dangers of Mythologizing God

What is the Balancing Act Between Iconography and Aniconism?

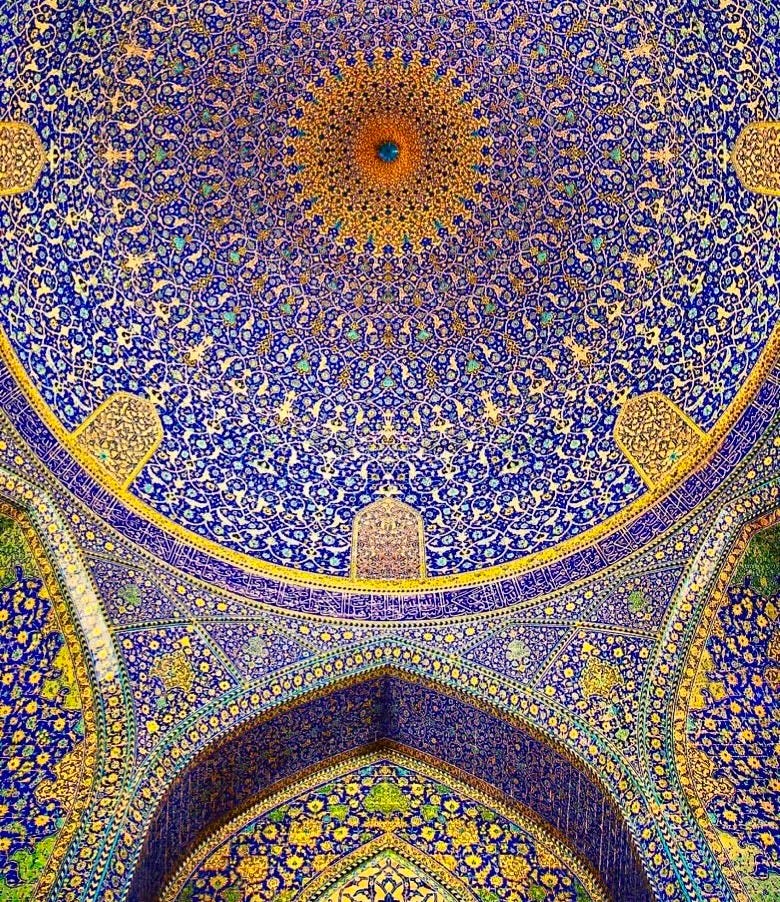

Religious art has long been a powerful tool for teaching, inspiring, and preserving faith. From the luminous mosaics of Byzantine cathedrals to the intricate tilework of Islamic mosques, art can both elevate the spirit and anchor a community’s identity. Yet, this very power carries a risk: when divine revelation is translated into visual form, it can cross an invisible line—shifting from faithful representation to imaginative myth-making.

Over time, repeated visual depictions can subtly reshape the way the faithful understand the divine. An image may begin as an attempt to convey a theological truth, but successive interpretations, embellishments, and stylistic conventions can lead to distortions. This is how, for example, some medieval paintings of the infant Jesus present him not as a child, but as a miniature adult—reflecting theological intentions of portraying wisdom and divinity, but creating imagery that, in hindsight, feels awkward, comical and in some cases offensive.

From Revelation to Mythos

The danger here is twofold. First, such art can detach the believer’s imagination from the textual or historical reality of scripture, encouraging a “mythos” that exists alongside—or even above—the original message.

Second, when these visual interpretations are taken as authoritative, they risk crystallizing theological misunderstandings, that the appeal of artistic brilliance may sway our reasoning away from the difinitive reality of scripture.

A good example of this comes from Nuremberg, Germany, while observing the grand scale of St. Sebaldus Church, I noticed a piece of art that, technically speaking, shouldnt be there!

In a medieval Lutheran church—born from the Reformation’s impulse to reject Catholic excesses—you can still find artwork affirming Marian theology, this painting depicted the assumption of Mary, a concept rejected by most Protestants, yet such a painting is in one of the most recognised German medieval churches of Germany.

While this might seem like a harmless relic of pre-Reformation art, it says something profound about the role of visual culture in shaping theological memory.

Through imagery, certain doctrinal emphases can survive and even thrive in contexts where they are no longer officially taught.

The art itself becomes a theological teacher, one that bypasses official creeds and sermons to lodge ideas in the believer’s mind.

What I find even more interesting about the theological dangers of mythologizing the divine is how the Quran affirms the exact painting that I am pointing out as a false teaching:

In Surah Al-Ma'idah 5:116, the Quran claims that Allah asked Jesus:

"Did you ever ask the people to worship you and your mother as gods besides Allah?"

And what do we find in the painting?

Three individuals (Mary, Jesus and The Father) being levelled in the skies as visually equal.

Many claims of truth are being affirmed in this one painting alone that not only go against the teachings of biblical scripture but also create a false narrative that unbelievers can use to claim the religion to be false.

Yet, Catholics still want to affirm this to be true because they are influenced more by the theological after-thoughts of tradition then the scriptural historicity.

It isn’t a suprise for Catholics to be accused of worshiping Mary when they build Marian theological concepts that make Mary come across as a worshiped subject of the faith.

But what is more confusing: why is this in a Lutheran Protestant church!?

Either way, with the Lutheran Marian example, the image becomes more than an aid to devotion—it becomes a formative force in itself, potentially reshaping the contours of faith.

For believers, this can be enriching, but it can also open the door to disillusionment if later study reveals the divergence between the art-inspired image and the textual truth.

This gap between perception and doctrine can weaken the credibility of the faith in the eyes of its adherents, particularly those who value historical and theological precision and consistency.

It is essential for a religion to understand the need to maintain to that which is true if they wish to defend the faith, otherwise, the muddied waters of mythologisation will make the faith confusing to non-believers or even damning to the opposition of the faith itself.

Aniconism Safeguards Against Mythos

It is in this light that the practice of aniconism (the avoidance of figural depictions of the divine) reveals its wisdom. Prominent in Islamic, Jewish, and certain Byzantine Christian traditions, aniconism seeks to guard against the human tendency to contain the infinite within finite imagery. By avoiding direct representation, these traditions sidestep the pitfalls of outdated or misguided portrayals that can later be seen as comical, culturally alien, or theologically problematic.

Instead, the divine is suggested through abstract, geometric, or calligraphic art forms. In Islamic architecture, for example, intricate arabesques and Quranic calligraphy convey a sense of the divine’s order, beauty, and transcendence without risking a concrete image that might mislead or limit the believer’s conception of God. This not only preserves theological accuracy but also keeps the focus on the transcendent, ungraspable nature of the divine.

Aniconism Can Make God Impersonal and Incomprehensible

The challenge with strict aniconism lies in its underlying assumption that the divine must remain perpetually beyond human grasp. This raises profound questions about soteriology (the doctrine of salvation) and our relationship with God. If we insist that God is wholly transcendent and incomprehensible, we risk creating a theology where humanity is trapped in an endless cycle of works-righteousness - attempting to bridge an unbridgeable gap through ritual and good deeds. This stands in tension with the Christian understanding of incarnational theology, where God specifically chose to make Himself knowable through the person of Jesus Christ.

The theological implications are significant: If God is truly unknowable, how can we have the personal relationship that Scripture promises? The doctrine of the incarnation - God becoming flesh and dwelling among us (John 1:14) - suggests that while God's full nature may transcend human understanding, He has deliberately made Himself known and accessible. This presents a particular challenge for Islamic theology, which maintains both the absolute transcendence of Allah while attributing to Jesus (Isa) miraculous qualities that border on the divine - a theological tension that remains unresolved in Islamic thought.

Consider: If we take aniconism to its logical conclusion, we might inadvertently support a deistic view of God - one who is so transcendent and removed from creation that meaningful relationship becomes impossible. This theological tension manifests clearly in Islamic prayer traditions (Salat), where the emphasis on precise ritual requirements suggests an understanding of divine-human interaction that differs markedly from the intimate, relational approach found in Christian theology.

Islamic prayer, with its meticulously prescribed movements, times, and conditions, reflects a theology where divine accessibility is highly structured and mediated through specific formal practices. The gravity attached to these requirements - exemplified in hadith like Sahih al-Bukhari 552 which states "Whoever misses the afternoon ('Asr) prayer, it is as if he had lost his family and property" - suggests an understanding of God as primarily approached through careful adherence to prescribed forms rather than through direct spiritual communion.

This stands in stark contrast to the Christian conception of prayer as an ongoing dialogue with a personally present God, epitomized in Paul's instruction to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thessalonians 5:17) and Jesus's teaching that true worship is "in spirit and truth" (John 4:24). The difference illustrates how aniconistic principles, when taken to their fullest expression, can shape not just visual representation but the entire theological framework of divine-human relationship.

This perception of God born from aniconism can inadvertently create a spiritual paradigm where God's transcendence becomes a barrier rather than a bridge. When we emphasize God's otherness to such a degree that we can neither picture nor approach Him except through strictly regulated rituals, we risk fostering a theology of perpetual unworthiness - where humanity stands always at an unbridgeable distance from the divine. This is perhaps the deepest theological danger of strict aniconism: in our zealous effort to protect God's transcendence, we might inadvertently deny the very intimacy and accessibility that makes faithful relationship possible. It creates a theological framework where we are forever unworthy of divine communion, trapped in endless cycles of ritual observance rather than embracing the transformative reality of God's desire for relationship with His creation.

In conclusion, this tension reveals a critical theological balancing act:

Iconography, when faithfully rendered, can illuminate our understanding of divine revelation and foster personal connection with scriptural truth. However, it risks mythologizing the faith when artists and interpreters allow human imagination to supersede biblical authority. The danger lies not in the images themselves, but in elevating artistic interpretation above scriptural witness.

Aniconism serves as a theological safeguard against misrepresentation, anchoring worship in transcendent truth rather than human depiction. Yet taken to its extreme, it can create an artificial distance between Creator and created, potentially undermining the intimacy God himself initiated through the Incarnation and covenant relationship.

The main problem with the movement of aniconism is the ideology in which it has influenced: Iconoclasm (that all forms of iconography are wrong and/or sinful)

The worst examples of this are of those of other religious faiths systems (typically ideological extremists) who go out of their own way to destroy the art of other faith systems.

Ultimately, the ideal lies not in wholly embracing or rejecting either approach, but in maintaining their proper theological tension. We must protect both God's transcendent mystery and His self-revealed accessibility - allowing art to serve as a bridge to understanding while ensuring it never becomes a substitute for divine truth itself.

Art can profoundly inspire and instruct, but when religious communities treat images as definitive truths rather than interpretive aids, the danger of mythologization grows. At worst, the visual “mythos” can become so culturally ingrained that it overshadows the textual foundation, creating a faith based more on inherited imagery than on scripture.

The challenge, then, is balance: to allow art to enhance devotion without letting it redefine doctrine, and to remain vigilant about the ways our creative expressions shape our theological imagination.

In many cases, as aniconism demonstrates, the wisest choice is to let the divine remain unseen—so that faith rests not on the contours of an image, but on the substance of revelation.

Be Part of The Discussion

One of the central aims of these articles is to spark meaningful conversation around the intersections of religion, theology, and philosophy within the framework of Christianity. I warmly invite readers to share their thoughts and engage in respectful discussion in the comments below, helping to cultivate a space where rigorous thought and sincere belief can meet in pursuit of truth.

Let’s create theological discourse in the comments below!

Weekly essays?

The trouble isn’t that art lies, it’s that it tells the truth with an accent, and after a few centuries the accent becomes the whole language. That’s how you end up with Protestant walls quietly hanging Catholic theology, and nobody notices until a Quran verse points it out. The Reformation may have burned plenty of saints in paint, but it still let a few slip past customs. Aniconism tries to solve this by banning the gallery altogether, but push it too far and you get a God so distant you need a lawyer, an appointment, and three notarized rituals just to say hello. The Incarnation was the opposite of that. God showed up with a face, not so we could freeze it in stained glass forever, but so we would stop mistaking the frame for the Friend.